When I worked with my co-author, Susan Titus Osborn, to write our Parables in Action series of first chapter books, it took time for us to develop our cast of characters. We brainstormed a unique and enchanting character trait for each that would easily identify them from book to book in the series. Here is a list of the quirky and fun characters that we created:

Parables in Action series

Cast of Characters

Suzie: This is the main character whose voice tells each story. She always prays when the situation gets sticky. Each story and each character is seen through her eyes.

Bubbles: This is Suzie’s best friend. Bubbles’ real name is Nan. She is a child actress on TV and appears in a different costume in each book because she is always practicing for her next new TV role.

Mario: Suzie’s friend, Mario likes to collect things. He’s very resourceful and comes up with all sorts of ways to raise money and fix problems.

Woof: Mario’s dog is named Woof. Woof is always running into a scene and barking, “WOOF!” at a key moment of the scene.

The Spy: He’s always writing spy notes in his spy notebook. The Spy’s real name is Larry. He always talks in secret code. For instance, “Iggle, iggle, snoogle, snoogle” means “yes.” When he says, “Ark, ark! Bam, bam!” he’s really saying, “Wow!”

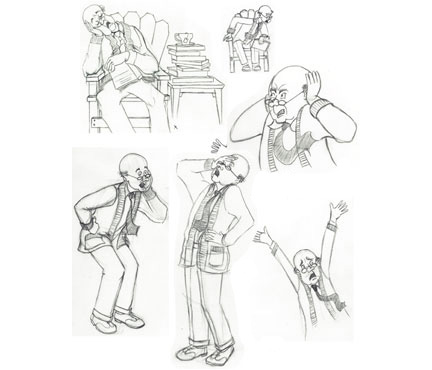

Mr. Zinger: This is the classroom teacher of all the kids in this series. He has a beard, wears a baseball cap, plays the guitar, and sings with the kids. Mr. Zinger’s character traits are based on my husband, Jeff, who teaches fourth grade and plays guitar while singing with his students!

As you can see, characters in kids’ books can be over-the-top funtastic!

So go ahead—have loads and loads of fun! Create a super duper scrump-dilly-icious cast of characters for your own stories and you’ll have just as fun inventing them as kids will reading about them.

-contributed by Nancy I. Sanders